- ホーム

- 学部・大学院

- 地球社会共生学部

- 教員一覧(地球社会共生学科)

- 教員インタビュー(桑島京子)

教員インタビュー:桑島京子

- MENU -

INTERVIEW 教員インタビュー:桑島京子

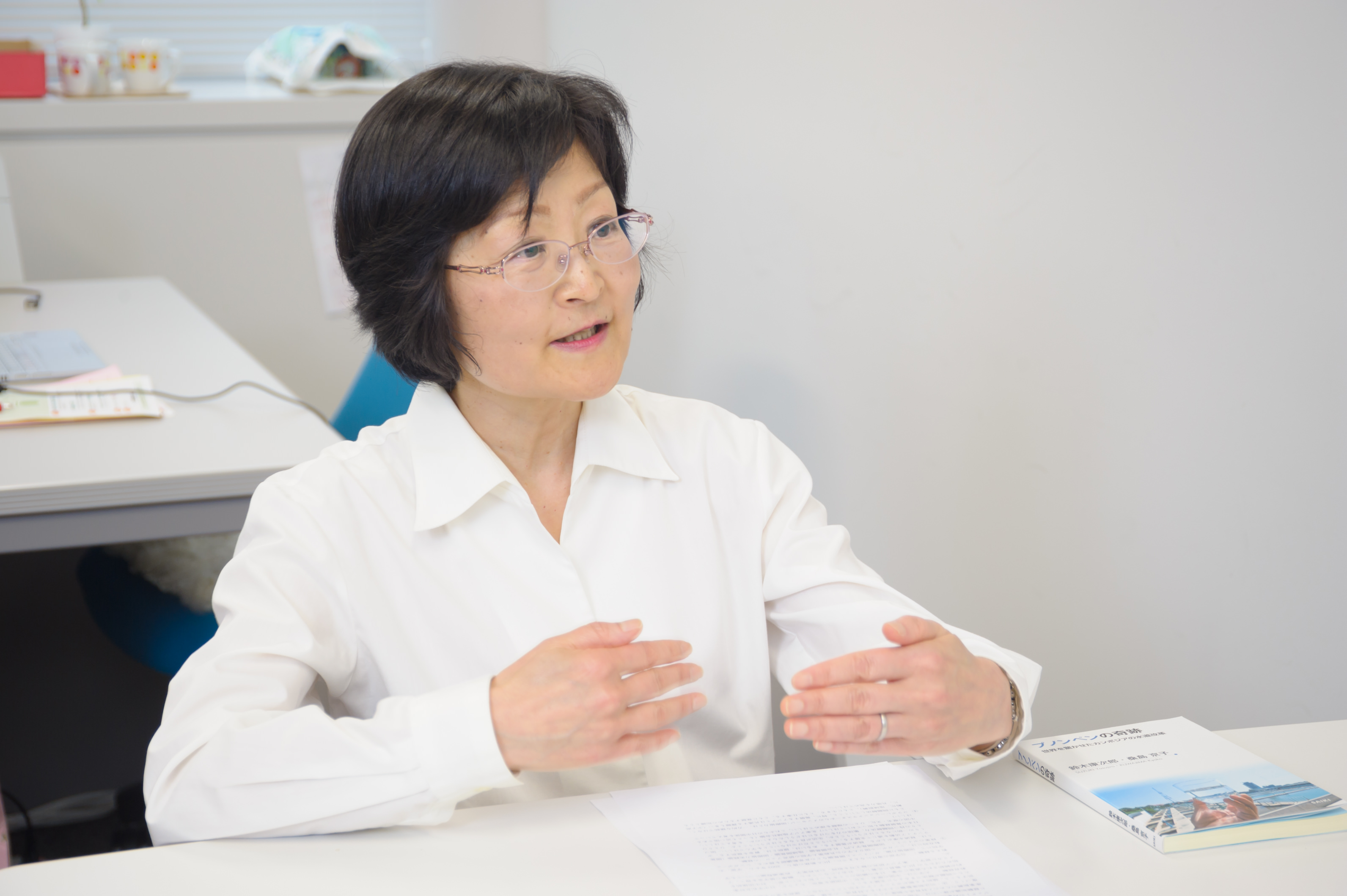

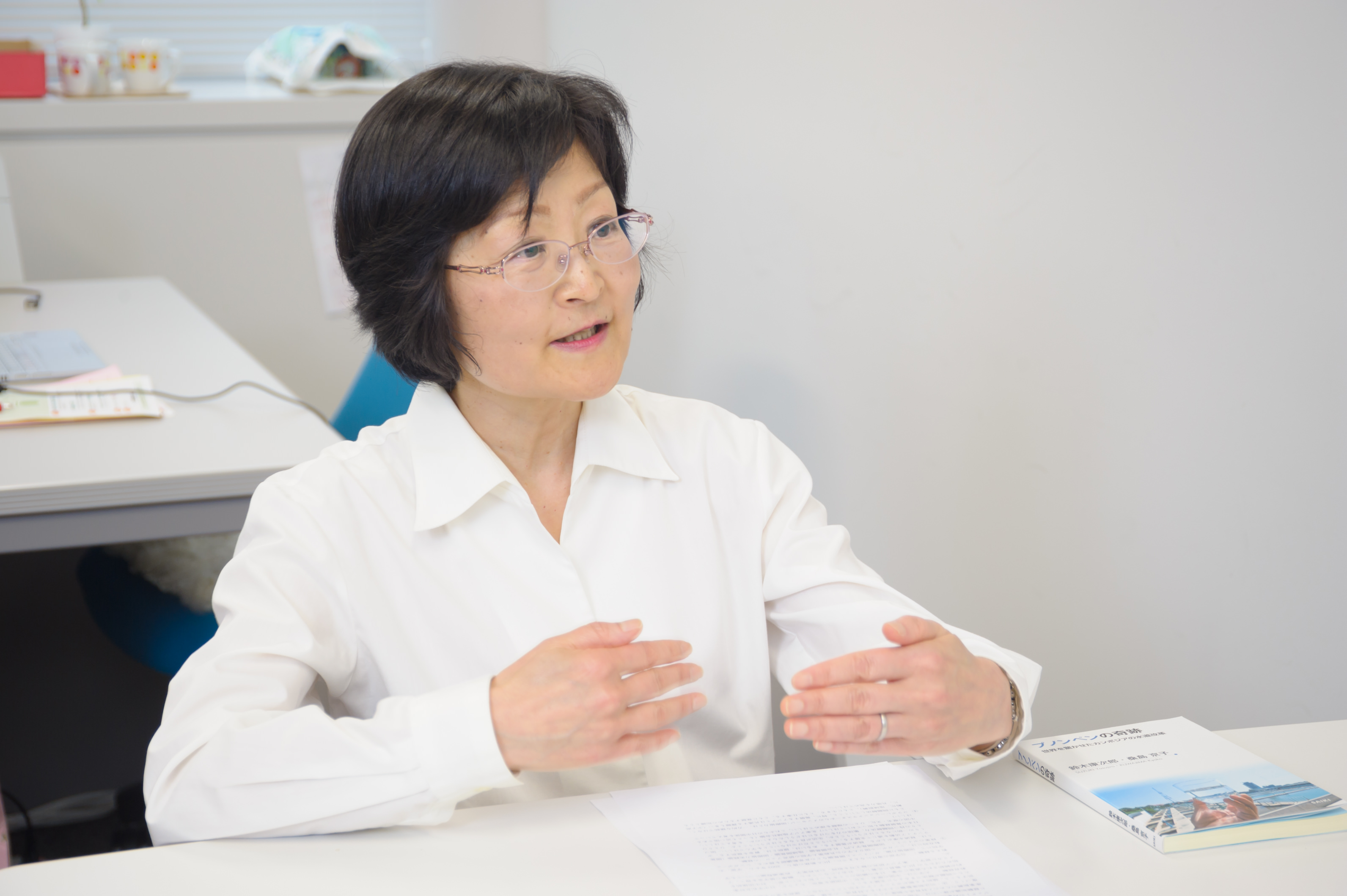

コラボレーション領域教授 桑島 京子

京都大学文学部卒業、ハーバード大学人文科学大学院東アジア地域研究専攻修士課程修了。大学卒業後、JICA(国際協力機構)に就職。中国や東南アジア諸国(タイ・カンボジアなど)を中心に、さまざまな援助プロジェクトや開発問題の調査研究に従事。JICAを退職後、本学の教授に。専門は「国際協力論」「社会開発論」「公共政策論」。主に開発途上国の政府能力の向上や公共サービスの改善に関心。社会インフラの整備にとどまらず、それらを維持・運営して、持続的な社会サービスとして提供しうる人材育成や制度づくりの事例から、成功や失敗の要因を見いだそうとしている。地域的な関心は東アジア。日本が発展途上だった時代からどのようにして発展してきたか、日本の開発経験にも関心がある。日本の援助のアプローチは自身の発展の歴史と深くかかわっている。

これまでの私の仕事

-中国や東南アジアを中心に援助の実務と調査研究にかかわる。さまざまな大学で、日本人学生、留学生と交流

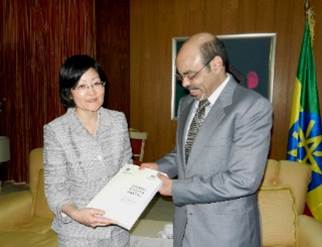

(画像:エチオピアに対する企業のカイゼン支援JICAの報告書を故メレス首相に手交する)

私は大学卒業後、中国に対する援助が始まろうとしていた時期にJICAに就職。36年間にわたり、中国をはじめとして、アジアやアフリカ諸国に対する政府開発援助プロジェクトの企画・実施や評価、開発問題の調査研究に従事しました。入社当初の担当は、主に中国からの研修生の受け入れや日本の専門家の派遣など、人の往来に関する業務が中心でした。いまからは想像しがたいですが、当時の中国は対外開放政策と経済制度改革を取り入れたばかりで経済水準も低く、日本などの資本主義の国に行くのも、外国人を受け入れるのも初めて、という人が多いでした。

日本からは、特定の技術や知識を熱心に学びとるだけでなく、市場経済に関わる価値観やルール、仕事の効率性や生産性など基本的なことから学んでいました。仕事を始めて5年目には北京事務所の駐在員になりました。まさに中国が歴史的な転換をしようとし、日本からの援助も急速に拡大したときで、大変おもしろい時代に対中援助に関われたと思っています。

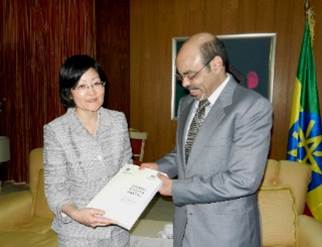

(画像:アジア開発銀行(ADB)・JICA研究所共催セミナーにてコメンテーターを務める(JICAプレスリリースより))

在職中の担当プロジェクトの対象国は、東・東南・南アジア、中近東・アフリカ、中南米にまたがりますが、とくに中国と東南アジア諸国(タイ、カンボジアなど)に対する数多くの援助にかかわりました。支援の内容は産業振興、地域開発やまちづくりのための人材育成や組織・制度づくり、法・司法制度の整備や人材育成など。インフラ整備などのハード面よりも、人材育成や組織や制度構築などのソフト面の支援に多く携わってきました。日本の援助戦略研究や、ソフト面の援助の事例から教訓や経験を引き出す調査研究にも関わりました。

また、JICA勤務の傍ら、東京大学や一橋大学、立命館大学などで、国際協力論、ガバナンスと開発論などを教えてきました。シンガポール国立大学のリ・クアンユー公共政策大学院に研究フェローとして出向する経験もしました。

私の授業はここが面白い

-援助は、自分たちで考え、問題を解決できるようにすることが最大の目的

授業で私が一番伝えたいことは、開発援助とは「経済水準を上げる」「経済規模を大きくする」「資金や技術を提供する」ということだけではありません。一番大事なことは、援助を受ける側が自分たちで必要なものを考え、問題を解決できるようにすることです。援助はいずれなくなるものという前提で取り組むべきで、援助する側はなるべく早く身を引いて、援助の受け手が自立することを考えておくべきだと考えています。

このことを考えてもらうため、授業では途上国の事例を使って学んでいます。例えば、カンボジアの首都、プノンペンの水道事業。現在、プノンペンでは先進国並みに質の良い水道水が使え、安く利用することができます。しかし、25年前は赤茶けた水が、1日に10時間程度しか出ないような状態でした。それを援助の力を借りて、10年以上かけてひとつひとつ改善していったわけですが、いったいどういうプロセスを踏んでいったのか。ほかの国でも役立ちそうな多くの教訓があります。

また、教育の普及を考えるうえで、発展の目覚ましいタイの経験も有益な事例だと思います。現在、タイの中学校の就学率は95%を越え、高校の就学率も約7割まできていますが、80年代の終わりごろまで中学校に進む児童は4割にも満たない状態でした。小学校までは行っても、そこから中学、高校の進学につながらない理由はさまざまで、学校の不足という施設の問題のみならず、学費が払えない、家事を手伝うほうが大事という経済的な理由のほか、進学したとしてもよい就職先が見つからない、学ぶ内容が実践的でなく役に立たないという地域的な理由、あるいはまもなく結婚するのにそれ以上の勉強は必要ないといいった価値観の問題などがあります。こうしたさまざまな事例から、どうして教育が普及しないのか、どうすれば改善しうるかを考えていけるような授業を目指しています。

受験生へのメッセージ

-これからの国際協力は、一方的に援助するのではなく、ともに共同して日本自身の問題を解決していくパートナーシップの関係になっていく

これまで行われてきた国際協力は、経済力や知識、技術の高い側が低い側を一方的に援助するというイメージが定着していますが、これからは、必ずしもそうではありません。実は、アジアの国々のなかには日本が抱える問題と同じような問題を抱える国があります。

例えば少子高齢化は日本だけの問題ではありません。65歳以上の人口が全体の7%を越えると高齢化社会、14%を越えると高齢社会といいますが、中国は間もなく高齢社会になりますし、タイもすでに高齢化社会です。タイの農村がこの問題についてどのように取り組んでいるかを見ると、年金制度などの保障は進んでいないが、一村一品やエコツーリズムの振興に高齢者が主体的に関わるなど、日本とはまったく違った視点での取り組みが行われています。

そのため、途上国を支援の対象としてのみ見るのではなく、パートナーとしてともに学ぶ、ともに開発する視点でとらえてほしいと思います。地球社会共生学部はそういった共感力を伸ばす学部だと思います。